We heard from Janine Roderick RGN, Head of Practice at SafeLives who explained the context charities and legislators are operating in, how Covid-19 has affected their work, and how new legislation is attempting to clamp down on domestic abuse.

Domestic Abuse in the UK

SafeLives are a UK-wide charity whose core mission statement is to end domestic abuse, for everyone, and for good. [1]

They work as an independent, evidence-led organisation with the voices of survivors driving their thinking. They work with other organisations across the UK to help form the response to domestic abuse.

Janine puts forward their mantra as “wanting what you would want for you best friend.”[1]

Their four key aims are to:

- Take action before someone is harmed or harms others

- Identify harmful behaviour and stop it

- Increase the safety for everyone at risk

- Enable people to live the life they want after the harm has stopped

The necessity of their work is highlighted by the following figures on domestic abuse in the UK:

- 2.4 million people aged 16-74 experienced domestic abuse in England and Wales last year

- That number is split into 1.6 million women and 786,000 men

- 2 women a week die at the hands of a partner or ex-partner

- On average 3 women a week commit suicide due to domestic abuse

- This totals around 300 deaths a year

This data is limited, however, as it is difficult to know how the numbers of over 60s that are affected by domestic abuse. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) only began collecting data on the 59-74 age group in April 2017.

However, Domestic Homicide Reviews show over a quarter of those killed by a current partner were aged over 58.

In 6 domestic homicide cases, it has been revealed that the perpetrator was the victim’s carer and no carer assessment had been completed.

The Impact of Domestic Abuse across a Life-course

Domestic abuse can and often does affect many across their entire life-course.

By the time children start school, on average at least one child in every classroom will have been living with domestic abuse since they were born.

Young victims are often exposed to other risks and harms, with 29% suffering from child sexual exploitation, and 15% being affected by gang violence.

Almost a quarter of young people exposed to these difficult situations begin demonstrating harmful behaviour, 61% of the time against the mother.

Many individuals and families experiencing domestic abuse have multiple needs, many of whom are ‘hidden’ from the necessary services.

Around 30% of children in households supported by an independent domestic violence advisor were not known to children’s services.

Those who do seek help often find themselves having to wait a long time before receiving support. 85% of domestic abuse victims seek help five times before accessing effective support.

On average, older victims experience abuse for twice as long before getting help as those under the age of 61. For marginalised groups, wait times are often longer to find suitable support.

In terms of perpetrators, only 1% of those who commit acts of domestic abuse receive any specialist intervention to be challenged to change their behaviour.

Segmenting Domestic Abuse

Gender

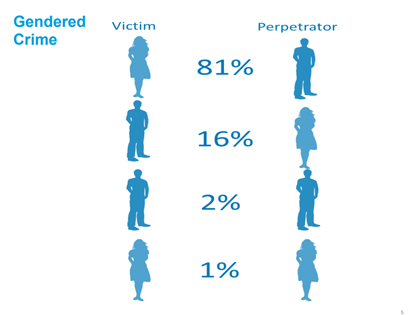

Janine highlighted that domestic abuse is a gendered crime, with the statistics being heavily skewed towards women victims.

The majority of older clients are also female, however there are much higher proportions of older men experiencing abuse.

Age

Over a third of male victims over the age of 60 had a female abuser, and over half were abused by an adult family member.

80% of older victims of domestic abuse are not visible to services, and of those who are visible, a quarter live with abuse for more than 20 years.

Only 0.7% of cases heard at multi-agency risk assessment conferences (MARAC) are referred by Adult Social Care. Over a third of MARACs had no cases referred in the past 12 months.

Disability

Disabled victims are more likely to be suffering abuse from a current partner, around 37%, compared to the 28% of non-disabled victims.

Disabled victims are more than twice as likely to be experiencing abuse from an adult family member than a non-disabled victim, with the statistics showing 14% and 6% respectively.

Only 7.2% of victims at MARACs were recorded as disabled, falling below the expected figure of 19%.

The Impact of Covid-19

There are several risk factors that have been amplified by the Covid-19 pandemic.

The co-related societal drivers of violence have massively increased, with unemployment disproportionately affecting women due to the gender gap.

Victims and survivors of domestic abuse are at even higher risk during this period with a rise in deteriorating mental health.

Not only are the risk factors being amplified, but the protective factors have also been impacted severely by the pandemic.

There is severe burnout amongst domestic abuse practitioners, with many suffering from burnout, declining mental health, and their overall wellbeing having dropped.

There has been an increase in referrals to all forms of support services, both statutory and voluntary-led. This includes telephone helplines, specialist services, and refuge.

The Domestic Abuse Act 2021

The legislation that has come into effect in 2021 provides a new statutory definition that emphasises domestic abuse is not just physical violence.

Domestic abuse can also be emotional, controlling or coercive behaviour, and economic abuse.[2]

Other key underpinnings of the Domestic Abuse Act 2021 include:

- Children are explicitly recognised as victims

- Creating a new offence of non-fatal strangulation

- Extending the controlling/coercive behaviour offence to include post-separation abuse

- Extending the offence of revenge porn to cover the threat of disclosing intimate images

- Eliminating the ‘rough sex gone wrong’ excuse in cases involving death or serious injury

- Making domestic abuse automatically eligible for special measures in the criminal, civil, and family courts

- Establishing the Domestic Abuse Commissioner

The role of the Domestic Abuse Commissioner is to be an independent voice that speaks on behalf of victims and survivors.

They will be able to use their statutory powers to raise public awareness and hold the government to account in tackling domestic abuse. [3]

The Bill also includes better protections for homeless victims, as well as children in refuges and safe accommodation.

It also tackles logistical issues, such as prohibiting GPs from charging a victim of domestic abuse for a letter of support, ensuring rehoused victims do not lose a secure lifetime or assured tenancy, as well as ending vexatious family proceedings. [1]

The act will also attempt to tackle perpetrators by:

- Prohibiting perpetrators of abuse from cross-examining their victims in person in family and civil courts

- Bringing the case of R vs Brown into legislation, invalidating any courtroom defence of consent where a victim is seriously injured or killed

- Enabling domestic abuse offenders to be subject to polygraph testing as a condition of their licence following their release from custody

- Providing for a new Domestic Abuse Protection Notice and Domestic Abuse Protection Order, which will prevent perpetrators from contacting their victims

- Forcing perpetrators to take positive steps to change their behaviours (such as seeking mental health support)

- Introducing a statutory duty on the Secretary of State to publish a domestic abuse perpetrator strategy [1]

Local Implementation

To help local authorities translate the new legislation into action, Safelives put together four steps to help integrate the processes into the current ongoing work.

Other suggestions to ensure that there is effective tackling of domestic abuse at a local level include both adult safeguarding and childcare services being present voices at MARACs every single time.

Forming local partnership boards to enable a cross-functional and multi-agency approach is also crucial, linking together key services that can help clamp down on domestic abuse, by both helping victims through care and targeting perpetrators through the appropriate authorities.

The final point Safelives make in their strategy to combat domestic abuse is simply to ask. Their ‘Reach In!’ campaign is focused on helping people feel prepared to ask if someone they’re concerned about is experiencing domestic abuse.

A survivor of domestic abuse, who is now part of the Safelives team, said the following:

“If you are a colleague of someone who you believe is being abused, ask them, say you will help. They may deny the abuse, say they don’t need help, but your offer will make them stronger in many ways.”[1]

They went on to say that knowing they have that option, and that they will be believed, is a major step in escaping the abuse.

[1] Roderick, Janine. 2021. Head of Practice, SafeLives. Safeguarding Adults and Domestic Abuse

[2] Gov.uk. 2021. Domestic Abuse Act 2021 [3] Domestic Abuse Commissioner. 2021. About us

Register FREE to access 2 more articles

We hope you’ve enjoyed your first article on GE Insights. To access 2 more articles for free, register now to join the Government Events community.

(Use discount code CPWR50)